Gabor Mate, physician and author, was hosting an ayahuasca retreat for psychologists and physicians with a group of Shibipo shamans. He had hosted these events for years. During the day, he would use his method of Compassionate Inquiry to help participants define the questions they had or issues they were hoping to address. On subsequent days, he would help them integrate what they learned from their ayahuasca journey. However, on this particular retreat, at lunchtime on the second day, the shamans came to him with a communal message, “You have a dense, dark energy our icaros (chants/songs) can’t penetrate. That energy pervades the room so it impairs our work with the others. We cannot have you there.” As he tried to negotiate with them to continue to be able to work with participants during the day they said, “Your energy would have a disturbing effect on the others, and more importantly, you would be absorbing their griefs and traumas. As a medico, you have obviously done that for so long, working with troubled people, and you have done nothing to clear that out of yourself. And, long before that, we all sense you must have suffered a big, big scare very early in your life; you haven’t gotten over it yet. That is why your energy is so dense.”

He shares this story in his book The Myth of Normal. As a fellow physician, I can certainly relate to absorbing griefs and traumas, working with troubled people, and doing nothing to clear it out.

beautifully shares the stories that he carries and some suggestions for systemically addressing post-traumatic stress in medicine. For me, the first, was a 2 year old with white-blond hair, breathing tube in place and bruises around her eyes ripening like plums. She died in the ICU two days later. We collect these stories as we go: brain bleeds, new cancer diagnoses, car, motorcycle and farm implement accidents, sexual assaults, intestinal bleeding, pregnancy complications, code blues. There are the ventilators and central lines and arterial lines. The chest compressions and shocks delivered. I still carry every one of these stories within me. I have never figured out how to lay a single one down. These stories all happened before COVID, which is to say I didn’t enter the pandemic with a full tank of gas.Four years ago, I was driving along the curves of County Road E, with multiple “Healthcare Heroes” signs along the road. I arrived at an eerily quiet Emergency Department, with a poster board on the wall that was changed multiple times a day discussing who we could test for COVID, what personal protective equipment (PPE) we could use and when, who we should see in a video visit versus face to face, and many other policies that were changing on sometimes an hourly basis. After my shift, I would go to my office and take a shower before going home even though I had only seen eight patients that day and none of them had COVID. It was a strange time, like seeing the ocean waves being sucked back to sea before a tsunami. I would regularly listen to EMRAP COVID updates to try to learn as much about caring for patients as possible as quickly as possible. Doctors in New York who were already drowning were sharing their experiences with COVID. In the intervening years, we went from “Healthcare Heroes” to forgotten or despised by the general public and also forgotten by the institutions we worked for and even our friends as well. Research shows that being unable to provide optimal care increases feelings of guilt, powerlessness, and frustration. We were unable to provide optimal care for three years. In fact, because of staffing issues sometimes we still aren’t. I have wanted to write about the intervening four years so badly, but I don’t remember most of the actual sights, sounds, smells, tactile sensations, and tastes of that time. I remember repeatedly peeling off personal protective equipment to answer phone calls, ventilators, arguments, dropping blood pressures, continuous interruptions, agitated patients, being asked to do the impossible over and over again, operating in crisis mode for three years straight, being everyone else’s pressure release valve without having a pressure release for ourselves. I remember being so, so angry. I have stories of specific patients with tragic endings, but that doesn’t convey how overwhelming and impossible everyday felt. When 2023 arrived and COVID was as over as it will ever be, the world eagerly and enthusiastically moved on. Some of us never did.

From September 2023 to March 2024, I dreaded going to work every single day. Opening my work email was a uniquely panic-inducing experience. I’m generally not wired to be an anxious person, so this was particularly unsettling. I went from crying at work about five times in my fifteen year career to twice in a week. As I noted a few weeks ago, dread’s a good sign you’re moving in the wrong direction. (For more detail,

wrote a great in-depth article about what he means) Was it burnout? A career that was no longer aligned with my values? Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS)? Who knows? In general, we doctors know just enough to be dangerous when we’re operating outside of our area of expertise, but we try to diagnose ourselves anyway. As a society, we have become really attached to psychological diagnoses, which can be helpful, but can divide us from the ways that we are all suffering.Prior to the pandemic, 16% of emergency physicians had PTSD. Research during the pandemic suggested that may have increased to 36%. Even some who do not meet the criteria for a formal diagnosis of PTSD have STS. STS is also known as compassion fatigue. I don’t love that term because it feels trivializing to me, as if the only trouble was that you were too tired to be compassionate. STS is ”a set of observable reactions to working with people who have been traumatized and mirrors the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder”. In 2017, 13% of emergency physicians had clinical levels of intrusion, avoidance, and arousal characteristic of secondary traumatic stress. 34% had clinical levels of symptoms in at least one category. Again, this was prior to the pandemic, a review published in 2023 showed that healthcare workers in Spain, Uganda, over half had high levels of compassion fatigue and another 25-30% had moderate levels. In other words, nearly 85% of healthcare workers in Spain had moderate to severe compassion fatigue, which they defined as a combination of burnout and STS. In Greece and Taiwan about half of healthcare workers had moderate compassion fatigue. From the available screening tools, I don’t have PTSD, but I definitely have STS.

You know who would be able to help me figure out what’s wrong? A psychologist. My husband and I watch Welcome to Wrexham together. The other night we were watching and they interviewed the team’s sports psychologist. As I understand it, sports psychologists try to help you get your head right so you can perform your best. I understand that the team in Wrexham has an unusual amount of attention and pressure on them. However, at the time of the episode filming, they were a fourth tier British soccer team. The consequence of them performing poorly is they lose a soccer game and community morale suffers.

I also work in a high pressure environment and the consequences of me having my head right are actually life and death, so I found the presence of the psychologist at Wrexham striking. I have never heard of any psychologist for physicians to help them function in their profession, aside from when a physician personally seeks one out, usually to address a crisis situation.

It can be difficult for healthcare workers to even recognize the impact of trauma on their physical health, emotional health, job performance, and relationships. Part of this is related to the hidden curriculum in medical education, which definitely encourages stoicism and discourages outwardly displaying emotion. The expectation is that even after a patient death that you take a few deep breaths and get back in the fray. That kind of approach left me very disconnected from my feelings, to the point that I really had to practice to figure out what I was feeling. It is also challenging to see because often it is not related to one specific incident, but rather the accumulation of large and small traumas over time. For example, though I have received some pretty serious threats from patients in the ED, I don’t have flashbacks or nightmares related to that specific incident. Instead it showed up for me as anger, helplessness, blaming others inappropriately, feeling isolated, and emotional exhaustion.

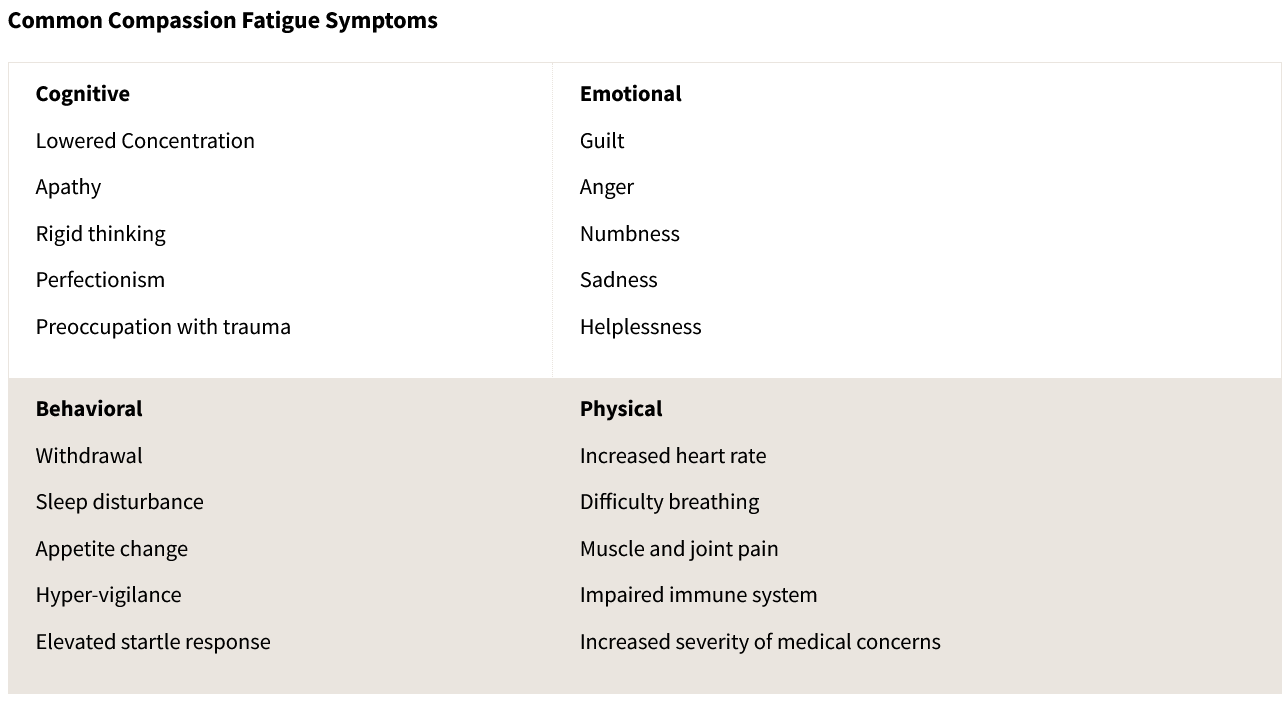

Traumatized people have a hard time operating at their best. The challenging emotions I was dealing with make it really difficult to find compassion or go the extra mile when someone needs that. In PTSD, in addition to the emotional symptoms and the anxiety and depression, there are the physical symptoms: pain, startling easily, avoiding triggers, numbing. As you can imagine if the hospital is the site of your trauma and you are continuing to try to work in a hospital, important challenges arise for both physician and patients. Here is a list of common PTSD symptoms:

Here is a list of symptoms of STS:

How does this look in real life? It looks like increased parental burnout and child abuse, child neglect, spouse conflict, and substance abuse. It looks like lower job satisfaction, increased turnover, and reduced professional commitment, and worsening compassion fatigue is associated with decreased quality of care.

How do we really address this? Increased workload, long working hours, and increased number of patients were predictive of developing compassion fatigue. That means healthcare organizations need to staff in ways that reduce overwhelm rather than maximize profit. Similarly, “HCPs [healthcare providers] identified that while there were plenty of wellness resources provided by healthcare organizations to support mindfulness, there was a lack of practical and pragmatic resources for social and emotional support, work-life balance, and remuneration.” This means building connectedness both within and outside the hospital, supporting people when they need to rest and recover with pay. People also need to be paid enough that money is not an additional stressor.

Would physicians be open to engaging with a psychologist or other mental and emotional supports? During the time pressure of a work day, I’m sure not. If it was an additional uncompensated requirement, no. If it was an expected part of their job and compensated as such, I think many, if not most of us recognize the dense energy we carry around and never clear out. I think we can agree these symptoms make less effective and compassionate physicians, but even more important, these symptoms leave us feeling like fractured and fragmented human beings.

Wrote a long response to this that disappeared into the belly of Substack’s poor editor. Probably better that way. As a medic in Viet Nam war I saw sensory maiming and death. I was able to leave the service damaged psychically but able to survive. I know that I’m not strong enough to survive what you experience.

Stones

I will not leave the imprint

of my feet

into the stones of time

I will not tilt up

the stone monolith

reaching for the firmament

There will be

No stone burial marker

In the grass of the moment

I will be free

To not exist

Leaving no stones

Wow! Terrific writing Amy! 👏 When I was training to be a clinical psychologist back in the 1970's, I never heard the word "trauma". As I have come to understand that concept better over the last 15 years, it has transformed my understanding of human beings and their suffering/pain. If one has their own trauma compounded by their professional training, well what would we expect? Exactly what you have written so well about here.