PTSD in Healthcare from an Organizational and Personal Perspective

How I Learned About Intrusive Thoughts and Current Assessment of Threat

“So, like, I don’t think I meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD…”

A funny, high-pitched noise emitted from my therapist, “Eehhhmm…”

“Ok, so you disagree…”

My therapist had thoughtfully read an article I wrote about diagnosis that resonated with her experience as a mental health professional. I was echoing that with my own personal experience and continued, “If I had been diagnosed with PTSD, I suspect I would be able to generate more compassion for myself, but on the other hand, I could just be more compassionate toward myself.”

In the few months we have worked together, we haven’t really delved into diagnosis because the lumping and splitting of diagnosis wouldn’t necessarily clarify the strategies or support I needed, but having me vocalize nearly the exact opposite of her professional assessment left her needing to clarify. We discussed that though I could learn skills to develop compassion for myself regardless, that I do have complex PTSD. I was reminded that the doctor who has herself for a patient has a fool for a doctor and a fool for a patient.

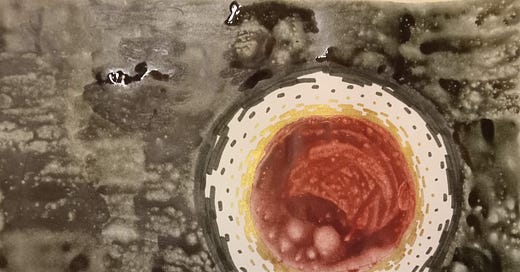

Given that I have tried to assess myself for PTSD enough that I thought I didn’t meet the criteria, the diagnosis wasn’t entirely unexpected. On the other hand, that diagnosis hasn’t changed the stories I tell myself in the ways that I expected. On a positive note, I realized that there was a reason I’ve only wanted to make art, work out and play outside. Working out and playing outside were always what I wanted to do. The art has been totally new over the last couple years. I had sort of suspected that my dive into art was, in part, a way of seeking external validation, seeking self-worth through achievement because I no longer have this automatic external validation-getter the word doctor hanging from me all the time. That’s an incomplete story. My brain is smart. It was self-medicating in a very savvy way to deal with suffering.

On a less positive note, in what is probably a surprise to no one except myself, that magical self-compassion didn’t come through as I had hoped. I found myself comparing myself to some folks online who have made a C-PTSD diagnosis the cornerstone of their personal identity. Wondering, “Ugh, am I like that?!?!” (Yes, I am aware that’s horrible!) Then I found myself comparing myself to my peers and wondering why I was the weak one who ended up with PTSD, while everyone else is “fine” even though many of them were exposed to the same, if not more intense, situations.

PTSD in the Healthcare System

I found myself curious about how PTSD is different in healthcare workers than it is in the more commonly portrayed experience of military veterans. Logically, it seems there would be some similarities, but also important differences in comparison to the more commonly depicted military experience. Even before the pandemic, 15-17% of emergency physicians met criteria for PTSD. Research during the pandemic has shown widely varying rates of PTSD in healthcare workers, but research specific to emergency physicians suggests rates as high as 36% during the pandemic. Overall, a metaanalysis (study compiling the results of many studies) found that 34% of healthcare workers had symptoms of PTSD and 14% had severe symptoms. These rates of PTSD are similar to rates of Vietnam veterans (with studies ranging from 18-30%).

Similar to Vietnam veterans I think healthcare workers are also facing challenges reintegrating into society at large. Soldiers in World War II certainly experienced PTSD, and the collective understanding of the purpose and value of this suffering at least limited the re-traumatization during return. When they returned, Vietnam veterans found that their suffering was viewed as meaningless and that they, themselves, were villainized.

Healthcare workers have seen a similar shift in the collective understanding of the value of our work, a shift in how valuable the collective views our sacrifices to be, and a shift in how meaningful we view our own suffering to be.

In addition, moral injury is common both in military and healthcare work environments. The concept of moral injury originated in studying the experience of combat military veterans. Researchers have consistently found that veterans who experienced moral injury were more likely to experience mental illness, including PTSD, but it remains controversial whether it is a neurologically separate process. Moral injury has been described as resulting from betrayal by an authority figure in a high-stakes situation. I have used the word abandonment rather than betrayal to describe my experience, but I have thought a lot about the fact that there isn’t one person that I can go to for repair or justice because there were so many layers from organizational to governmental that left us behind (or at least that’s how it felt).

In the study I reviewed, healthcare workers had higher rates of moral injury during COVID than prior research had found in military veterans. The authors noted, “This may be attributable to HCWs feeling betrayed by members of society, government, and/or healthcare colleagues/leaders, observing patient care practices interpreted as substandard, and perceiving that persons internal or external to healthcare systems are behaving individualistically instead of pro-socially in a time of crisis.“

But this isn’t just about me, it is a topic that the general public has selfish interest in as well. A study of ER nurses from back in 2003 showed that 20% of them considered changing jobs as a result of a traumatic experience. The literature I reviewed didn’t specifically address career change due to trauma during the pandemic, but I would be shocked if that number wasn’t substantially higher than 20% now. PTSD also has an impact on the quality of healthcare provided. PTSD increases compassion fatigue and burnout. It decreases productivity. PTSD is also associated with increased patient falls and medication errors. In other words, as I mentioned the other day, the health of the healers is an important indicator of the health of the society and we all need to be invested in addressing trauma due to providing healthcare.

Unsurprisingly, a lot of the factors that predispose people to developing PTSD are beyond individual control, but they are within organizational control. “Heavy workload, poor training on traumatic events, and lack of cohesiveness among workers,” were factors that occurred before a traumatic event that increased the likelihood of PTSD. Stress due to organizational and staffing issues leave workers feeling unvalued and increase conflict in the workplace, both of which increase the likelihood of PTSD.

Heavy workload after trauma, working in unsafe situations, dealing with stress by avoiding or withdrawing, anxiety, and burnout also increase the risk of PTSD after a traumatic event. The unrelenting workload for years certainly left little room to process traumatic events. And I can think of little more effective at signalling to staff that they are unvalued than by putting them in potentially life-threatening situations through an inability to provide personal protective equipment.

In addition, after trauma, lack of manager and colleague support and lack of debriefing increase the risk of PTSD. “By literature, social support is a known predictor of occupational stress in emergency care workers and it is defined as ‘the feeling that one is cared for and has assistance available from other people’ and ‘that one is part of a supportive social network’” Italian researchers d’Ettore, et al found in a 10 year review of studies about PTSD in healthcare workers. In addition, they note, “...the more emotional support received from supervisors and colleagues (i.e. acting as a confidant, listening and offering sympathy to the victim of traumatic episode) after a traumatic event, the lower the risk of developing PTSD status for HCW (healthcare worker).” Social support is so significant that people with a low level of social support were nearly 6 times more likely to develop PTSD than those who had a high level of social support.

I really felt the scarcity of social support. It was definitely a major leadership challenge, because of the prolonged duration of traumatic events and because the help that was offered by necessity had to occur during shift and left you feeling further behind or occurred on a day off and interfered with rest and recovery. Unless the support occurred within the context of paid time off, it wasn’t going to feel very supportive. I imagine many people also felt like me and didn’t ask for any help because we didn’t know what to ask for. On the other hand, one easy way to support people is to recognize them as unique individuals and their contributions. Over the course of the three years where the pandemic felt high intensity, there was no meaningful recognition of what we were doing, no increase in paid time off, no increase in pay, no hazard pay, not even a face to face “atta-girl”.

Years later, I listened to a podcast on how to support healthcare workers during the pandemic. (The podcast was created at the beginning of the pandemic and I was listening to it last summer.) They mentioned that “sometimes the agenda has to change”, meaning that sometimes you have to let people vent and drive the meeting agenda rather than continue on with business as usual. This is important leadership both to show that you value your staff as people, but also because it raises your awareness of the realities they're facing in their day to day work. Hearing someone say that brought tears to my eyes because it felt quite far from my experience. This echoes research-based evidence too. An environment in which people can express feelings and experiences of a stressful situation has been found to be protective against developing PTSD.

d’Ettore et al. had recommendations for preventing PTSD in healthcare workers. They recommended:

Focusing on organizational predictors of PTSD:

Heavy workload

Poor training on traumatic events in hospital settings

Lack of cohesiveness among hospital employees

Workplace violence

Lack of social support from managers and colleagues

Focusing on worker vulnerabilities (Age and gender appear to increase risk. However some research suggests younger age is a risk factor and others suggest older age. Most research suggests women are at higher risk of PTSD).

Counseling for healthcare workers who experienced traumatic events

Theorell provided further evidence-based recommendations in an editorial, written in 2020 as guidance for hospital leaders at the beginning of the pandemic. These included:

Flexible work schedules that adapt to ever changing conditions. Up to and including 4 hour shifts with 4 hour rest periods during the most exhausting periods.

Sleep hygiene with Circadian shift cycles and good opportunities for undisturbed sleep.

Social support to family members; worries for family members could add to the caregiver’s health deterioration

Participation in decision making

Facilitation of good coping mechanisms

Facilitation of cultural experiences during leisure time

Clearly, there is room for improvement in nearly all healthcare organizations in these regards. Focus on productivity above employee wellbeing creates a morally and emotionally injurious environment. Most emergency medicine groups recognize that it gets harder and harder to maintain one’s wellbeing doing high-stress shift work. They decrease the number of shifts needed to be full time after a certain number of years of service. Counseling, on the other hand, often isn’t as accessible as it should be and is the employee’s responsibility to pay for themselves unless it is immediately after a stressful event or sometimes if an employee is in severe crisis. Unfortunately, this isn’t the real world. My experience was that I didn’t realize the full impact on me for a couple years after the peak intensity of the trauma. When I finally reached out to the Employee Assistance Program, they said, “Ok, you should find a therapist through your insurance.” Unfortunately, by that point I no longer had health insurance.

My Personal Experience

Gathering information is a big part of how I make connections and meaning, so I got to work. When I looked at the Cleveland Clinic’s website about complex PTSD, I found that it is often caused by genocide, slavery, and prolonged family violence (child abuse, partner violence). It really didn’t feel like my suffering stacked up. I know it’s not the Suffering Olympics and that the suffering I endured was enough to at least temporarily “break my brain”, but the brand of trauma, poverty, and abuse I am exposed to in my small town ER feels like quite a different brand of suffering than the violence of penetrating trauma (gunshots and stab wounds) of big city ERs, much less the long-term personal experience of violence and betrayal at the hands of an abusive family or during war or genocide.

Another interesting part of the Cleveland Clinic article was that feeling trapped or unable to leave is often part of complex PTSD. Looking at it from the outside and with hindsight, I can see that, of course, I had an opportunity to leave that others in family violence, war and refugee situations would not. But if you had asked me in the heat of the moment, could I just leave, I would have said no. I don’t know if that was fear about not having money, some sense of honor or duty, not wanting to abandon my colleagues, or feeling obligated to stick with the sunk costs of the time and money I put into my education. All I can say is that it felt impossible to consider any possibility beyond putting one foot in front of the other to continue on as I was. Interestingly, one study found that physicians were more likely than nurses to experience higher levels of functional impairment due to post-traumatic stress symptoms. This surprised me because nurses are much more likely to experience workplace violence. I wonder if it has to do with this feeling of not being able to leave because of debt or sunk costs.

I’ve been trying to understand PTSD in more detail and to find out more about the unique aspects of PTSD in healthcare workers. PTSD is characterized by three main components:

Re-experiencing traumatic experiences in the present through intrusive thoughts, flashbacks, or nightmares

Avoidance of people, places, and objects associated with the traumatic event/events. It can also include avoidance of thoughts and feelings.

A sense of current threat

I understood these criteria academically, but in my experience, it’s hard to identify your own thoughts as intrusive, because they are just…your thoughts. I definitely noticed the pandemic continuing to occupy a disproportionate amount of mental real estate compared to friends and colleagues who do the same job. With a little more understanding of what’s going on, I can also see avoidance in my desire to stay away from the hospital or the strong reaction I have to putting on scrubs. But the most fascinating part of my research has been in regards to a sense of current threat.

The other night my mom was asking me about what brought up the sense of dread of work for me. I didn’t have a clear concept of why I felt it. I thought maybe it’s a fear of feeling overwhelmed or that I would be in situations where I wouldn’t be equipped to do what needed to be done (because hospitals were full or specialists were unavailable). After a little more research, I think what it really is, is that my ability to assess current threat is totally out of whack. Unless the Emergency Department is totally slow to the point of time dragging because there’s nothing to do, my mindbody is convinced that an overwhelming situation that I will be unable to manage is imminent. The tricky thing in the ED is that you don’t have any way to predict or prepare for what it will actually be like. Most likely, it will be totally fine and manageable, but there have always been rough days that are totally overwhelming and unmanageable and you don’t know when those are coming. Because of that, you can’t reality check and say, “You’re out of that situation, it’s not going to happen again”, because it very easily could.

Researchers also noted that, “The negative effects of altered threat perception may not be immediately noticeable at the level of weeks. Instead, individuals’ sense of current threat may constitute a reactive state [pattern of brain activity that is engrained through repetition] rather than a driving factor in the persistence of PTSD symptoms.” That echoes my experience. I didn’t notice my altered threat perception until I returned from a 6 month sabbatical and felt a disproportionate physical response to putting on scrubs and returning to the hospital.

Within about 6-9 months of the most intense suffering during COVID, I already had a sense of post-traumatic growth. To be honest, I started noticing that well before I came to terms with the more disordered response to suffering during the pandemic. My temperament tends to default toward, “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” with a small side of existential crisis. That said, I have noticed a huge difference in my ability to recognize and express my emotions, the depth and nuance of my spiritual life and creativity, and an acceptance of the healthy interdependence that is needed for both strong relationships and personal wellbeing. I found this Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory a fascinating measure of where I’ve been and where I am now.

Ultimately, it seems that this diagnosis did lend me some clarity, if not compassion. The most important points of this little research adventure for me are recognizing that someone else may need to help you recognize that your thoughts are intrusive, that our ability to assess the current threat may be “off” for quite a long time, and how important moral injury and social support are in the development of PTSD. None of us make it through life without some trauma, but hopefully building those social supports can help us achieve healthy interdependence that allows us the maximum growth with the minimum of disorder from the trauma.

Hi Amy, I resonate with so much of what you write about and THIS, in particular, is so timely. I'm a nurse with over 4 decades of experience, the past 15 with the VA. I started seeing a therapist last month for some work-related issues. After a few weeks I gently asked, "so... what is my billable dx? " PTSD, she said. I thought I was doing okay, just more anxious than usual, sleeping poorly, nightmares. But yeah, I met all the criteria. And here we are. Thanks for being here and sharing from the heart.

Yes and thank you for writing this all out!